People don’t usually come to tarot looking for therapy.

They come because they want guidance, meaning, or a sense of contact with something beyond themselves. Sometimes they want answers. Sometimes reassurance. Sometimes they just want to know that what they’re feeling makes sense.

And yet, if you read tarot for any length of time, you quickly notice that what arrives in the room often looks a lot like therapeutic material.

People bring grief, heartbreak, identity crises, illness, estrangement, and moments where their life no longer fits the shape it used to. They ask about lovers, work, purpose, loss, and direction. They speak about fear, hope, shame, longing, and confusion in a space that is intimate and emotionally charged.

So the question isn’t really whether tarot is therapy.

The question is: what responsibility comes with holding that kind of space? Especially when tarot sits outside the formal structures, training pathways, and ethical frameworks that govern psychotherapy.

This is where things get complicated.

On the one hand, tarot is often dismissed as frivolous, manipulative, or dangerous: the domain of fortune-tellers, charlatans, or the occult. This tension is well known within tarot communities themselves; as Marcus Katz (2009) dryly put it, “half your market thinks you are evil.”

On the other hand, tarot readers frequently do work that overlaps with meaning-making, emotional processing, and inner change. Although in their case, this is often without the cultural legitimacy or protections afforded to therapists. Ethnographic research with tarot and spiritualist workers supports this, showing how practitioners commonly occupy roles that resemble healing or therapeutic labour, even when they do not frame their work in clinical terms (Lavin, 2021).

This is where comparisons with therapy start to matter and where they also begin to unravel.

Therapy itself is not a neutral or untouchable good.

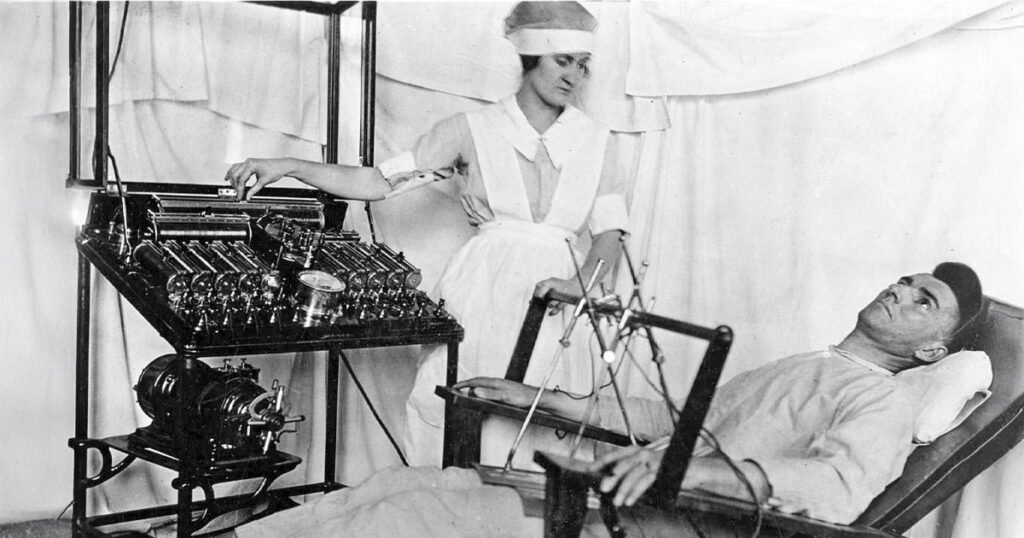

The history of mental health care is far from clean. It includes coercion, pathologisation, and the medicalised control of (mostly) women’s bodies. Not to mention practices once considered legitimate that are now widely recognised as harmful.

So the issue isn’t as simple as tarot versus therapy, or trained versus untrained. The issue is more about power, stigma, and the uneasy place tarot occupies between the mystical, the psychological, and the socially taboo.

Tarot, therapy, and the problem of legitimacy

In contemporary culture, tarot often ends up circling the edges of psychotherapy

This isn’t accidental. In many places, tarot is far more accessible than counselling or psychotherapy (Farley, 2009). A tarot deck is inexpensive. Sessions are easier to find. Waiting lists are shorter. And for many people, tarot offers a way into reflection and meaning-making that feels less intimidating and less clinical than conventional talking therapies.

This accessibility is part of its appeal. But it’s also where some of the tension begins.

Within regulated therapeutic contexts, there has been a growing call for more flexible and creative approaches. Some psychotherapists have argued that the courage to explore methods beyond strict clinical norms is vital to the profession itself (Vargas, 2019). Arthur Rosengarten (2000), for example, has written about using tarot within the therapy room as a more direct route to unconscious material – one that can be less threatening, less hierarchical, and less bound to predictable conversational patterns.

From this perspective, tarot isn’t positioned as a replacement for therapy, but as a symbolic tool that can support psychological exploration in ways that are faster, richer, and more economical for the client.

At the same time, tarot’s relationship with therapy has often been shaped by a desire for legitimacy.

Throughout its history as an esoteric tool, tarot was repeatedly reframed in the language of higher-status systems, like romanticised ancient wisdoms, esoteric sciences like the Kabbalah, and psychology (Decker, Depaulis, and Dummett, 1996). While at the same time being distanced from lower-status associations such as fortune-telling. This pattern continues today, particularly when tarot is presented as “therapeutic” or “psychospiritual” in order to separate it from images of superstition, manipulation, or spectacle.

This is understandable in the context where Tarot has long been marginalised, dismissed, or treated with suspicion. Aligning it with psychology can feel like a way to protect both the practice and the practitioner.

But this move isn’t without its complications.

When tarot is framed too closely as therapy, it can blur important boundaries around responsibility, authority, and care. Tarot readers are not regulated in the same way therapists are. There are no shared standards of training, no consistent ethical frameworks, and no formal mechanisms of accountability. While the same is, to some extent, true of counselling and psychotherapy in the UK, the absence of clear structures becomes more visible and more risky in unregulated spaces.

This doesn’t mean tarot readers are inherently less ethical than therapists.

Nor does it mean therapy itself is immune to harm. The history of mental health care includes coercive and abusive practices that were once considered acceptable, particularly toward women and other marginalised groups.

What it does mean is that tarot occupies a paradoxical position.

It is often dismissed as irresponsible or dangerous, while simultaneously being asked to do significant emotional labour. It is expected to provide insight, reassurance, and meaning, while being denied the legitimacy afforded to other forms of care. And in navigating this tension, tarot practitioners are left to negotiate questions of power, projection, and responsibility largely on their own.

Authority, power, and the problem of projection

One of the most persistent concerns raised about tarot, particularly when it brushes up against therapeutic territory, is the question of power.

Unlike counselling or psychotherapy, tarot is largely unregulated. There are no shared standards of training, no compulsory ethical frameworks, and no formal consequences when boundaries are crossed. Critics often point to this freedom as evidence that tarot is inherently unsafe, or that it leaves vulnerable people open to manipulation.

There is some truth in this concern. But it’s also worth holding it alongside a more uncomfortable reality: ethical safety has never been guaranteed by professionalisation alone.

Mental health care has its own history of harm, coercion, and abuse which is often carried out under the authority of institutions, credentials, and clinical legitimacy. The presence of regulation does not automatically neutralise power; it simply organises it differently.

What makes tarot distinctive is that power dynamics are often more visible.

Tarot operates through symbolism, ritual, and interpretation. It carries cultural associations with mystery, intuition, and the unseen. Scholars of divination have long noted that practices like tarot function less as the delivery of fixed truths, and more as forms of meaning-making shaped through interaction, interpretation, and relationship (Jorgensen, 1984).

In this context, it’s easy for authority to gather around the figure of the reader when readings are framed as accessing hidden knowledge, spiritual truth, or forces beyond the everyday.

Sociologists of esotericism have noted that tarot practitioners sometimes emphasise supernatural ability or ritual performance in order to establish credibility (Lavin, 2021).

This isn’t necessarily evidence of deception. Forms of “fronting-out” authority, or the performance of expertise, confidence, and legitimacy, are common across professions, from medicine to academia to law. What differs is how these performances are culturally read.

When a physician performs authority, it tends to register as competence. When a tarot reader does the same, it is more easily framed as manipulation, spectacle, or trickery. As Randall Styers notes, the category of “magic” has long carried pejorative weight in Western culture, marking certain forms of knowledge as suspect or dangerous (Styers, 2014).

At the same time, performance carries ethical risk.

Arthur Rosengarten (2000), writing from within psychotherapeutic practice, describes the danger of what he calls “shamanistic transference”: the projection of special or magical powers onto the practitioner. In tarot, this can show up as the belief that the reader knows better than the client, sees further into their future, or holds authority over their decisions.

This is where dependency can form. It’s not because tarot is uniquely manipulative, but because uncertainty makes people vulnerable, and symbolic authority is compelling.

These dynamics aren’t unique to tarot. They exist wherever people seek guidance, meaning, or reassurance. But tarot’s marginal status amplifies them. Because it sits outside mainstream legitimacy, tarot readers are often left to navigate these power imbalances without the support of shared language, training, or ethical infrastructure.

Some practitioners respond by distancing tarot from anything “magical,” reframing it entirely in psychological terms. Others lean into mysticism, emphasising intuition, spirit guides, or divine authority. Both moves are attempts to resolve the same tension: how to hold authority without becoming authoritarian, and how to offer insight without taking power away.

There isn’t a single right answer.

What matters is awareness. Of projection. Of dependency. Of how easily meaning can harden into certainty when someone is in pain. And of the responsibility that comes with being trusted at moments when people are disoriented, grieving, or afraid.

For me, ethical practice begins here. Not in pretending tarot is neutral, harmless, or purely symbolic, but in staying alert to the ways power circulates in the room, whether we name it or not.

Where this leaves my practice

So when people come to a reading wanting certainty, wanting to know what will happen, or what they should do, I don’t hear that as a problem to correct. I hear it as a moment where something matters, and where the ground feels unsteady.

My work with tarot sits inside that space.

I don’t see tarot as therapy, and I don’t see it as a substitute for therapeutic care. But I also don’t pretend it isn’t intimate work. It often takes place at moments of grief, rupture, transition, or deep questioning. At those moments where people are already touching something vulnerable and alive.

Because of that, I hold tarot as a practice of relationship rather than authority.

I’m not interested in deciding anyone’s future for them, or positioning myself as the one who knows.

At the same time, I don’t shy away from clarity, directness, or difficult truths when they arise through the cards. Tarot isn’t always gentle. Sometimes it’s sharp, confronting, or inconvenient. What matters is how that information is held, and who it ultimately belongs to.

For me, ethical practice means staying alert to power without pretending it doesn’t exist. It means naming uncertainty rather than covering it over. It means trusting that the person in front of me has their own intelligence, intuition, and capacity for discernment — even when they can’t quite access it yet.

Tarot, at its best, becomes a conversation between two forms of knowing. Not a verdict. Not a prescription. Not an abdication of responsibility. But a space where something already present can be seen more clearly.

If a reading leaves someone feeling more connected to themselves, more able to listen inwardly, to tolerate complexity, to make empowered choices, then I trust I’ve done what I’ve needed to do.

Anything beyond that isn’t mine to decide.

References

Decker, Ronald, Thierry Depaulis, and Michael Dummett. A Wicked Pack of Cards: The Origins of the Occult Tarot. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Farley, Helen. A Cultural History of Tarot : From Entertainment to Esotericism. London: I. B. Tauris, 2009.

Jorgensen, Danny L. ‘Divinatory Discourse’. Symbolic Interaction 7, no. 2 (1984): 135–53. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.1984.7.2.135.

Katz, Marcus. Tarot in the Marketplace: Half Your Market Thinks You Are Evil. Marketing Considerations for Professional Tarot Readers. Tarot Professionals, 2009.

Lavin, Melissa F. ‘On Spiritualist Workers: Healing and Divining through Tarot and the Metaphysical’. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 50, no. 3 (2021): 317–40.

Rosengarten, Arthur. Tarot and Psychology: Spectrums of Possibility. 1st ed. St. Paul, Minn: Paragon House, 2000.

Styers, Randall. ‘Magic and the Play of Power’. In Defining Magic: A Reader, edited by Bernd-Christian Otto and Michael Stausberg, 1st edition., 255–62. Critical Categories in the Study of Religion. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2014.

Vargas, H. Luis. ‘Enhancing Therapist Courage and Clinical Acuity for Advancing Clinical Practice’. Journal of Family Psychotherapy 30, no. 2 (2019): 141–52.